The Supreme Court’s recent 5-4 decision not to intervene in two partisan gerrymandering cases obviously has ramifications for redistricting and future congressional elections.

But it could also impact the Electoral College. The ruling effectively opens the door for states to gerrymander presidential elections.

How to Gerrymander Presidential Elections

Each state has a number of electors equal to its representation in Congress — two votes for the Senate, and a number based on the state’s House seats. For all but two states, the winner of the popular vote in the state also wins all the electoral votes.

However, each state has the flexibility to allocate their electoral votes in different ways. An alternative proposal would allocate two votes at large for the overall winner of the state and the rest of the electors would go to the candidate that wins each of the state’s congressional districts. This is actually how Maine and Nebraska currently split their electoral votes.

Some argue that if this system were rolled out nationwide it would be less likely to result in a candidate winning the national popular vote while losing the Electoral College.

However, our analysis shows that for the two most recent elections where this happened — in 2000 and 2016 — the popular vote winner would have still lost under this system. In fact, it would have caused the popular vote winner to lose the Electoral College in 2012 as well.

This is true for one simple reason: gerrymandering. And it would only get worse if states are now allowed unfettered gerrymandering and the ability to gerrymander presidential elections.

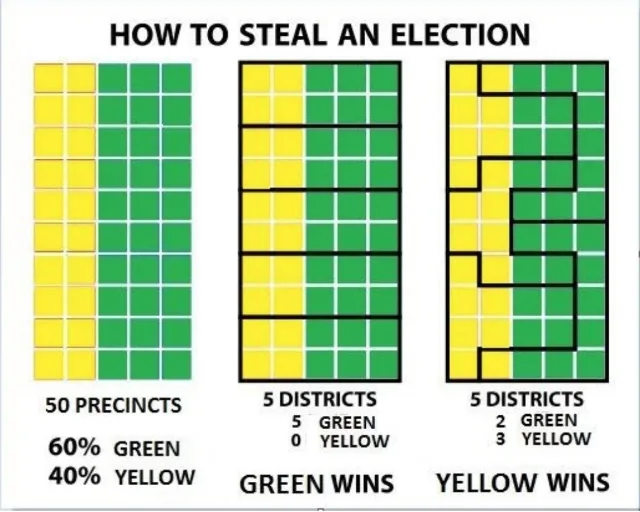

Partisan gerrymandering allows the clever drawing of district boundaries, so that the party in power can minimize the impact of the rival party.

As the simple chart below shows, the party in power can even draw the lines to win a majority of House seats despite winning fewer votes:

The pressures for states to gerrymander would increase dramatically if congressional districts determined control of the White House as well as control of the House.

Because of the way gerrymandering works, the vast majority of voters would live in “safe” congressional districts, meaning that voters would have even less incentive to turn out to vote. The handful of swing states that decide modern presidential elections would turn into a handful of swing congressional districts.